Robert Stubbs stood down as Chairman of the Forest Industry Contractors Association just six months into his tenure, after his business collapsed. The industry’s boom and bust cycle might have become as natural and unavoidable as the seasons but for Robert, and many others, the bust is personal, and permanent. Ian Parkes investigates in the second of this two-part report.

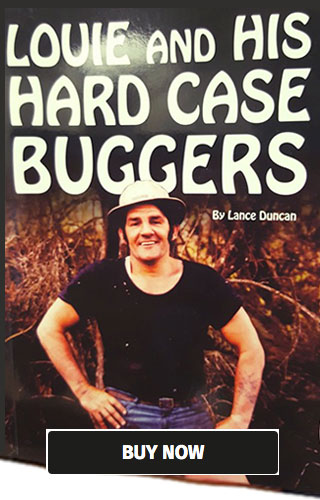

Two decades on in his career, Robert Stubbs (Stubbsy) had built a successful forestry contracting business employing around 70 people. In 2018 he won the Westpac Gisborne Business Leadership Excellence Award and Stubbs Contractors was a finalist in several other categories including Supreme Business of the Year. As outlined in part one of Robert’s story published last month, he had overcome massive personal setbacks, including an accident that left him confined to a wheelchair, and had ridden out earlier industry boom and bust cycles. He was a board member of the Forest Industry Contractors Association (FICA) and a key figure on the Forest Industry Safety Council (FISC) that had helped transform industry practices and worked at turning around its bleak safety record.

Then along came COVID.

“The industry came off that huge high just before COVID then, of course, the industry crashed as China started to grapple with COVID,” Robert says. “We were stuck with it for the following 12 months as the market never really bounced back after that. For the first time in a long time corporates laid off their core crews and I was a casualty of that with a couple of my contracts.

“I suppose this is where a lot of people start to slowly fall into that trap when the industry is not buoyant and it’s stop/start,” he says. What’s more, Gisborne has other issues that make trading your way through a bit harder.

“If it’s not market conditions, it's infrastructure that’s slowing it down or the port that’s slowing it down… and all the time you have got forest companies coming at you and reducing your production from 100 percent to 80 percent, asking you to pull back a dollar or so on your harvesting rates, so all of that is pulling back on your cashflow.”

Robert says absorbing the repercussions of a boom and bust cycle can easily set up an erosion of equity that undermines a business. It’s a slow increase in a slope that business owners don’t often see, or acknowledge, or not soon enough.

“It erodes the business’ ability to turn over equipment as it ages,” he says. “So then you start to hold onto it and you think, ‘oh well, I bought some good gear, that can last a bit longer, it can go another 4000-5000 hours longer’, but you are falling into the trap of holding onto gear that’s getting older and older, it’s depreciated, the values have fallen right out of it, the trade-in’s no good.”

The business’s equity erodes. That makes it harder to sustain long industry downturns as well as making it even harder to...